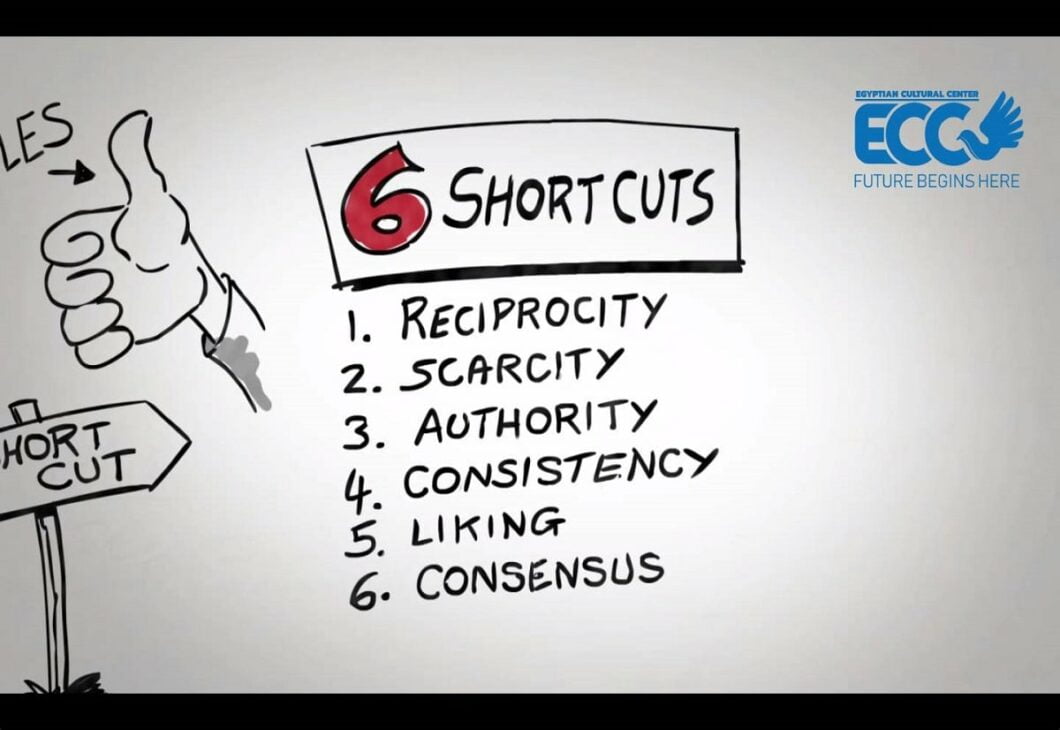

Six basic psychological principles that we use as shortcuts, and which can be exploited for persuasion: reciprocation, scarcity, consistency, social proof, liking and authority.

First idea: Always talk about rational reason and your unique selling point or why your opinion is brilliant.

We’re much more willing to do people a favour if they provide us with a reason – any reason like when a salesperson tells you that this skirt is a perfect fit for you and other prestigious women wear the same skirt.

Always give reasons why they should invest with your company or why you want to get their turn in a queue! Be reasonable for sure.

Provide presents and never forget that “the rule for reciprocation, which states that those who give first are entitled to receive in return.”

In an experiment to study this phenomenon, a researcher asked people queuing up to use a copy machine whether she could skip the line. She found that if she gave a reason – “May I skip the line because I’m in a rush?” – 94 % of people complied with her request.

If she gave no reason, only 60 % complied like may I skip the line?

But, fascinatingly, if she gave a nonsensical reason – “May I skip the line because I need to make copies” – 93 % still complied.

One example is the commonly abused “price indicates quality” shortcut.

People usually assume expensive items are of higher quality than cheap ones, and while this shortcut is often at least partially accurate, a wily salesman might well use it against us. For example, souvenir shops often sell unpopular goods by rising rather than lowering their prices and they appealed to be attractive because now they are expensive which means for many that are a good product.

Another law about the influence of favors is important to imagine if someone does us a favor and we do not return it, we feel a psychological burden.

This is partly because, as a society, we are disdainful of those who do not reciprocate favors; we label them as moochers or ingrates and fear being labeled as such ourselves.

For example, in a 1971 study by psychologist Dennis Regan, a researcher, “Joe,” masqueraded as a fellow participant and bought test subjects a ten-cent Coke as an unbidden favour.

Later on, it turned out that Joe needed a favour: he was trying to sell as many raffle tickets as possible to win a prize. Would the subjects help him out by buying some?

On average, the subjects who had received the unbidden Coke reciprocated by purchasing 50 cents’ worth of tickets – twice the amount compared to if no Coke was given. The feeling of indebtedness even seemed to outweigh likeability: some of the participants bought Joe’s raffle tickets even though they said they did not like him.

The dynamic is fairly simple to put to use: if you want something specific from a negotiation partner, start with an offer they are pretty sure to reject. Then retreat from your initial offer to what you really want. Your opponent will probably see this as a concession and feel obliged to make a similar one.

This strategy is often employed by labour negotiators, who start with extreme positions and then gradually retreat while extracting concessions from the other side.

However, researchers have discovered that there’s a limit to how extreme your opening position can be: if it’s too outrageous, you’ll be seen as a bad-faith negotiator, and subsequent concessions will not be reciprocated. The rejection-then-retreat strategy